Dennis Farber

Fear is Just Another Word for Someone Left to Please

I want to first address the title of this presentation, “Fear is Just Another Word for Someone Left to Please.” I do not want to sound coldly glib, because obviously, there are circumstances in which fear is the appropriate response.

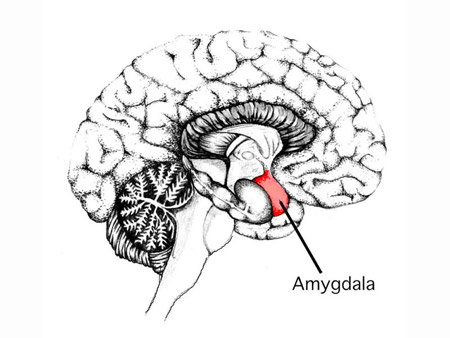

Fear is the brain’s biological response for survival, the amygdala on the lookout for threats. And, in a life threatening situation, it can be, well—a life-saver.

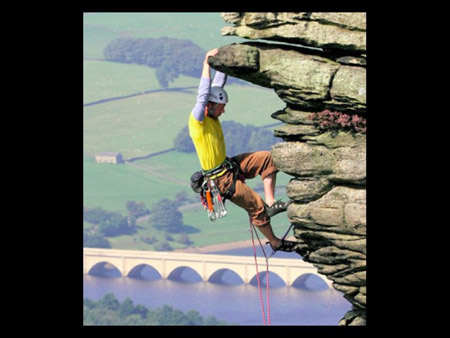

For the purposes of this talk—I am referring to the nature of fear as experienced in rock climbing, comparing that to fear experienced in creative practice within the privacy of one’s studio, and observing the differences and similarities.

We have all experienced fear, perhaps terror, that requires a courageous response in the face of danger and threat. And I do not want to diminish the very real experience of fear provoked by our inner lions and tigers and bears, oh my …

Rather, I would like to address how we might find the courage to act in the face of those fears, which can hamper our full and free creative expression.

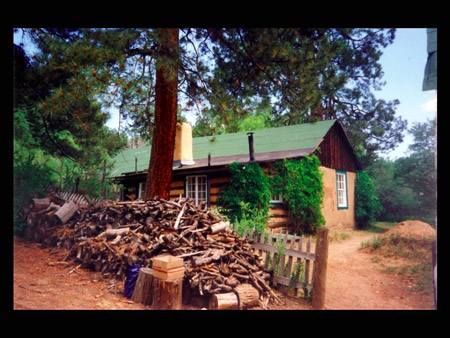

The art department of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where I was a professor, had full access to the D. H. Lawrence Ranch to run an intensive, two week summer sessions on topics of our choosing. The ranch is located in a remote mountain area north of Taos, NM. And, by way of a somewhat surreal and fear-provoking aside, students and teachers live in the housing units that were the original housing from Los Alamos Labs from the time the atomic bomb was being developed.

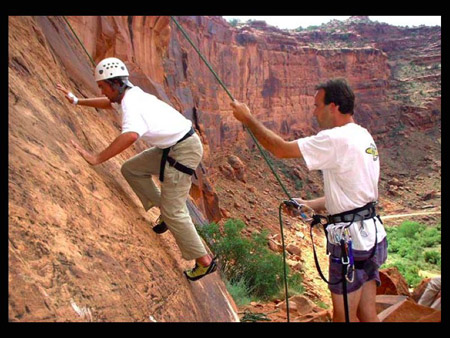

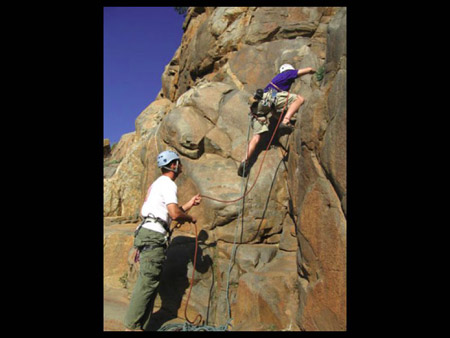

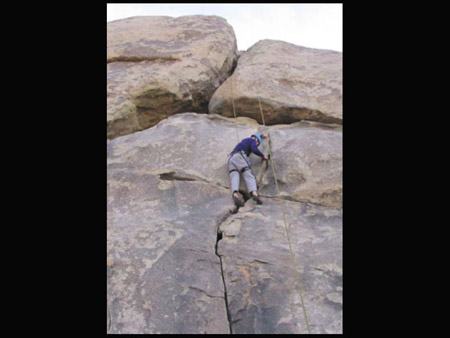

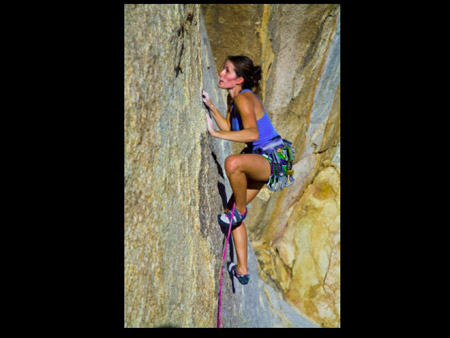

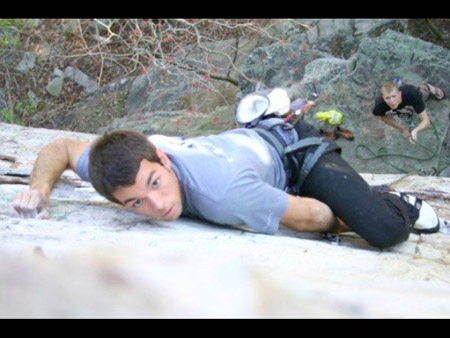

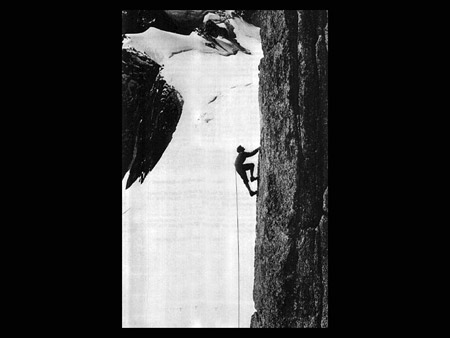

In 1994, I conducted a rock climbing/ART seminar/studio at the ranch called “rocks, smocks, brushes, and talks”, that was aimed at addressing fears provoked by external, physical dangers as well as by those fears generated internally.

I wanted to investigate whether lessons learned facing the fears of the external and physical danger of rock climbing could be transferable in any way to helping students face the kinds of internal/personal fears that arise in the studio.

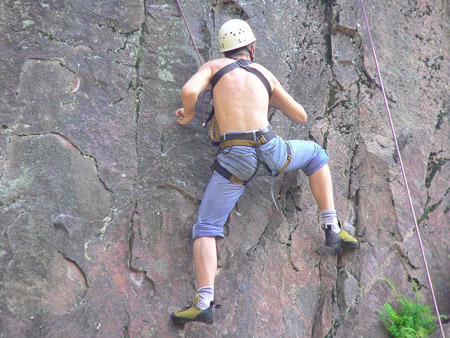

All twelve participants, a mix of graduate and undergraduate art students, were midway to advanced in their fine arts degree program—none had any previous rock climbing experience.

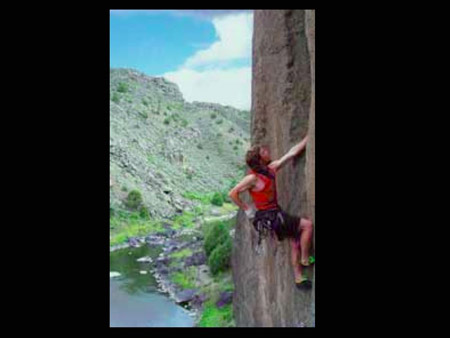

We spent each morning rock climbing at John’s Rock in an area along the Rio Grande. (I have always said teaching was as close to not having a job as I could get.)

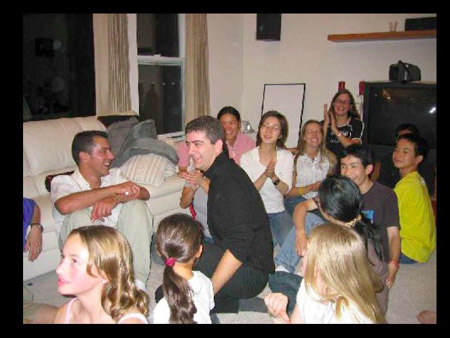

After a morning of climbing, afternoons were spent in the student’s respective studios—and we would come together as a group again most evenings for pot luck dinners and discussion about climbing, art, fear and whatever topics arose that caught our attention and kept the conversation going.

We also spent a few nights away from the ranch camping, as it is my experience camping reinforces the bonding and trust necessary for both rock climbing and creating an environment in which people feel safe enough to speak freely, openly and honestly, which was yet another kind of fear participants were asked to experience, face and address in our seminar.

Do physical risk and the fears associated with rock climbing have anything to teach us about the kind of fears associated with the creative process?

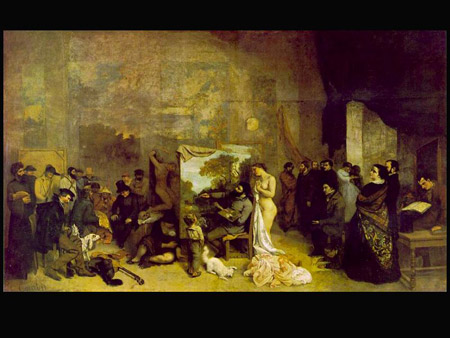

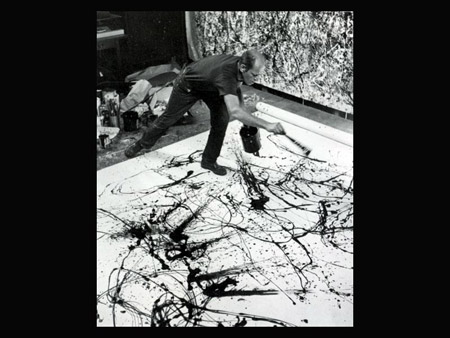

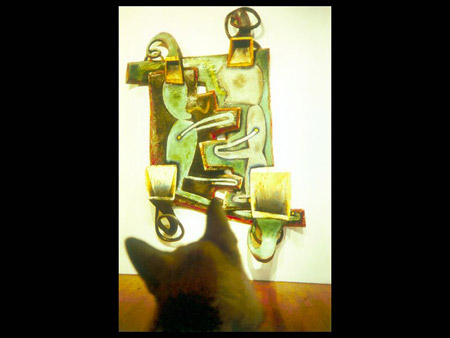

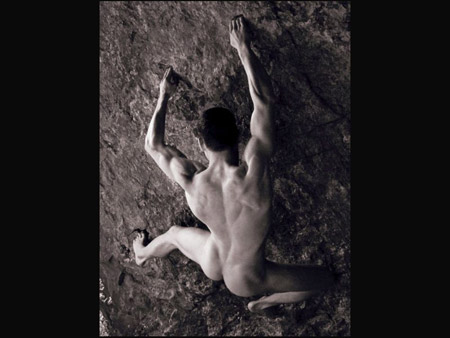

Other than Matthew Barney, who, in his debut at Barbara Gladstone Gallery climbed around the space naked, I cannot think of another visual artist who has referenced this sort of risky physical activity in their work. I know performance artists have cut, even maimed themselves, but, in comparison, I see that as spectacle, and not related to a studio practice. Aside from dancers, physicality and athleticism is not the stereotypical perception of an artist. But, through my predilection for both activities, I have been led to experience a number of similarities and differences that do seem to be transferable and useful metaphors for what happens in the studio. So, I am going to put forth some of my observations on the two activities, rock climbing and studio practice.

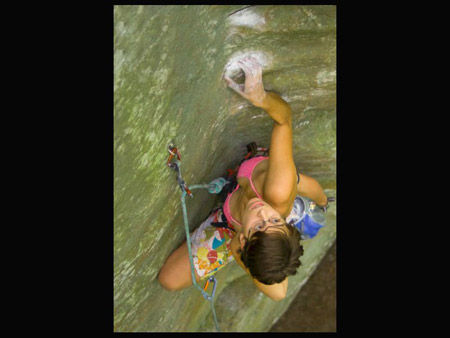

Safe rock climbing is necessarily a collaborative activity. There are those who “free climb” without any type of safety gear that might give protection should anything go wrong, but that is not an activity I endorse and the students did none of that.

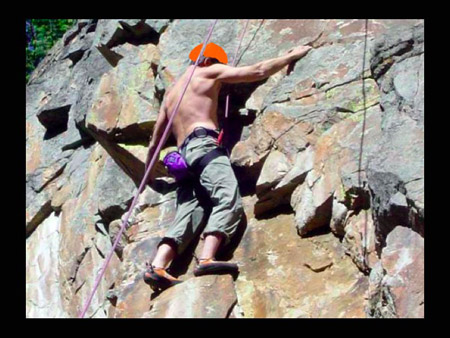

Climbers, to stay safe, are both physically and psychologically interdependent on one another’s skills. You must not only trust your own abilities, but the ability and judgment of your partner(s).

Climbers are literally linked by a lifeline in the form of a rope, and in the event one falters or falls, the other is there to stop or minimize any injury. Nobody tops out or succeeds without the help and support of others, and in fact, others have your life, literally, in their hands. Your expertise is essential, but useless without the cooperation and expertise of your climbing partner(s).

Studio practice is, for most of us, a solitary experience. And yet, there are intrusions, voices with which we are all familiar—internally and externally generated expectations concerning:

- the best way or

- the right way or

- the currently fashionable

- or critically acclaimed

- or worthwhile way …

- how the tried-and-true way might differ from an individual’s need to find his or her own way,

- the way that has yet been traveled,

- the way every artist must find for him or herself.

Add to this the accepted cultural belief that success is measured by the critical and or financial confirmation of others, and if you are not careful, you can find quite a noisy crowd in your studio. The stress created by ideals and expectations can easily undermine the critically important silence needed to develop and trust listening to one’s own creative voice.

In the studio, you are not tethered to anyone or anything—so you have only yourself to trust. Herein lies the problem.

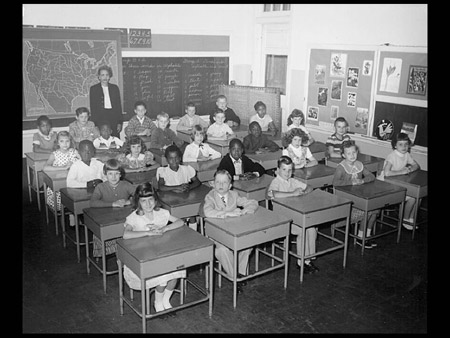

Years of formal education have, unfortunately, taught us not to trust ourselves. Ask a student in any first year university art class who among them can draw and few, if any, of their hands will go as high toward the ceiling as those asked the exact same question of in any first or second year elementary school class.

Kids just draw or paint. Big, little, any subject you might suggest or they can imagine. Unfortunately, confidence in their own ability drops with every year they progress through the educational system.

We have all experienced this—our confidence and exuberance quashed by the very system meant to help support our growth. Do not get me wrong. I am not making a case against education. I am, however, interested in education that helps support the kind of experimentation that allows for failure and encourages exploration without fear of approval.

I am certainly not immune to fear. None of us are. I am standing here speaking with outward confidence and yet doubt creeps in—maybe I am way off-base, maybe I will not be able to handle the question and answer period, what if my presentation seems trivial? But maybe, maybe what our creative work teaches us that transfers back outside the studio, in this instance to rock climbing—is that it is OK, be afraid and continue on. After all, we are emotional beings who laugh, cry, get angry, and are fearful. It is called being alive. And sometimes it is hard to be a person.

The fear of self-expression is real, even if it is not death defying or physically risky. We are fearful that we will not be able to meet our own expectations or those of others.

But isn’t the privacy of one’s own studio a space which allows us to exist away from the glare and to proceed as we please safely—free from the judgments of an unforgiving world?

No one is watching, no one has seen what we have done or might do—and yet we are filled with fear, often before we have even begun. Our studios are crowded with our projections of all those looking over our shoulders who we need to please.

It is in learning how to silence those voices, how to proceed in the face of fear and not knowing if or where the answer lies. The studio is a sacred space in which we can simply “be”—if we can allow ourselves that luxury. And if we do, we can carry that lesson outside the studio.

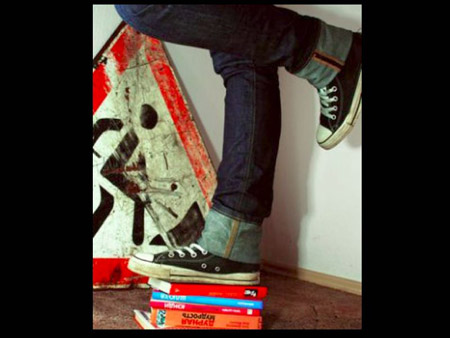

It is on the rocks that I was able to provide my students a laboratory in which they could experience the kind of physical fear response which stops us in our tracks—and through the experience of moving beyond that fear, they have a talisman which they can then refer to in the studio to help them deal with the psychological fears implicit in the creative process.

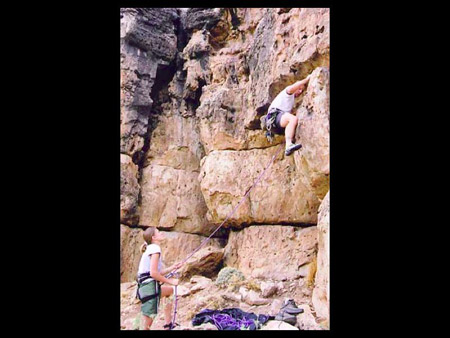

Rock climbing demands a basic knowledge of particular skill sets in order to ensure a safe experience. There are the inherent dangers, of course, not only of the physical climbing, but weather, human error and equipment failure. Prudence is necessary on a climb, even better, redundancy. The fact is, one can be seriously injured or die from a very short fall, often an unfortunate, but avoidable mistake.

None of the skills necessary to offset these possibilities can be learned as one proceeds on a climb. There is too much at stake. They all need to be taught and practiced over and over and over again before one gets to the rock face—no matter how simple the climb.

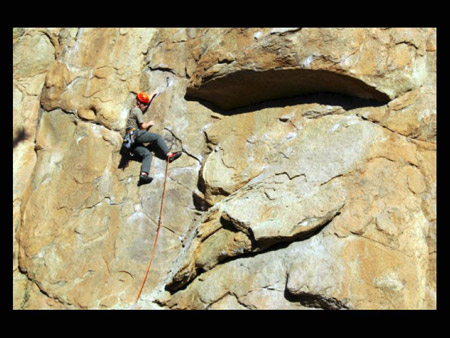

For instance, there is nothing in our day to day experience that tells us it is OK to step off a very steep, high rock face backwards, even if you’re wearing a harness with a rope attached. That first step is always the most difficult and scary—and the subsequent rappel has to be the result of practice, knowledge of equipment and teamwork. But you cannot take the second step until you take that first one. I am not saying do not be scared, but there is informed, prudent risk.

Climbers are not acting on faith in the face of fear, they are utilizing a set of skills to help ensure their safety. There are ropes, and harnesses, helmets, and fellow climbers, all with training to minimize risk and maximize chances of success.

And while individual artists have various levels of skills, knowledge and prior experience, and even a bag of tricks that might help them feel safely tethered—there really are no specific rules or particular skills that ensure one’s success in the studio.

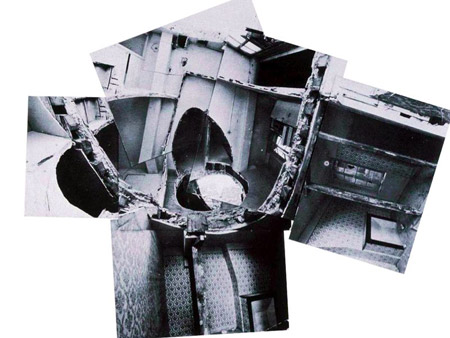

In fact, the creative process may be unique in that one learns what one is saying and doing in the process of saying and doing it. No amount of preparation assures a successful result. Of course, the same is true in climbing. But unlike climbing, in the studio, preparation is as likely to result in failure as it is success. And if one is truly taking creative “risks”—one experiences failure upon failure upon failure.

I say with no fear that artistic success is the result of multiple failures. Unlike rock climbing, failure is an integral part of success in creative practice, and though one might fear failure, there is no risk of not surviving failure in the studio.

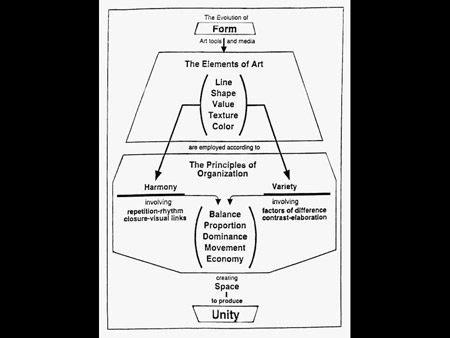

However, in the same way as learned techniques and rules can help ensure safety on a climb, analogous learned and practiced techniques and rules can create the sense of a safe atmosphere in the studio and critical acceptance beyond. Working within familiar techniques, according to formal, academic rules and cultural preferences is likely to help one reach a larger audience. Working in canonically accepted ways reduces both the anxiety of the artist and that of the viewer: everyone can feel at ease.

As I mentioned, rock climbing has inherent dangers that necessitate knowledge, skill, prudence, and adherence to the norm in order to help ensure success.

Studio practice also has dangers in the form of toxic materials, but they can be worked with and rarely result in the kind of bodily harm possible in rock climbing. But materials aside, unlike climbing, it is precisely the process of risk taking and deviation from the norm through which discoveries are made in the creative process. In order to take these risks, we cannot think about those “someones left to please.”

Deviation from the norm is the substance and foundation of western art history’s linear progression, the cultural expectation overlaid onto your creative practice, to position yourself as unique, to take precedents and apply the eccentricities of the present to create something new.

What are some other similarities and differences between rock climbing and art making that might help us face our fears and silence the voiceover about those we feel obliged to please?

Rock climbing involves a certain amount of physical dexterity and strength for which preparation is essentially mandatory. Painting has no such requirements or limitations. That, in and of itself, ought to be liberating.

Rock climbing has little tolerance for alcohol and/or drugs—though a cold beer after a long day of climbing is not a rare occurrence. The romantically held notion that mind-altering substances enhance not only the creative process, but the results is pure myth and equally out of date as the lone genius in the unheated garret.

I have pointed out some of the similarities and differences as related to risk-taking and fear between rock climbing and working in the studio. But, was anything we learned in our rock climbing/art making experiment at the D. H. Lawrence Ranch, really transferable and actually helpful in the studio?

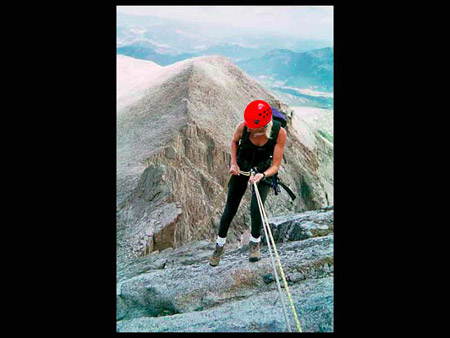

The most important and significant lessons that transferred from rock climbing to the studio have to do with comfort and adaptability. The first lesson that is dramatically experienced in climbing is that comfort holds little satisfaction.

What do I mean by that? One can finally, after much stress and exertion, and a good amount of anxiety and fear, get to a place on a rock face where one feels secure having solid hand and foot holds, a place to catch one’s breath, allow muscles to relax, the fear to dissipate, and let one’s heart beat slow and congratulate and bask in what was just accomplished. One should take a moment to look around, take in and appreciate the beauty of the landscape from the height achieved.

But if you want to finish the climb, there comes a time when you must leave behind that hard earned zone of comfort, and step back out onto the rock face not knowing if there’s any comfort awaiting you for the remainder of the climb, until you reach its conclusion. This is a very important and valuable lesson for the studio.

Admittedly, not all practitioners are interested in the discomfort certain studio processes promote, as not all climbers are interested in testing their limits of fear or exertion. And for them remaining in one’s comfort zone is the desired place to be. It makes for a successful day in the studio and on the rocks, and I see no fault with that.

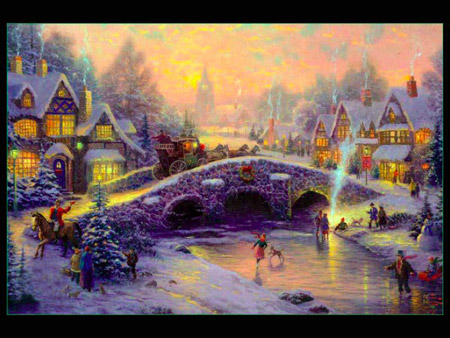

It could be said that risk and the fear associated with risk are not essential to or even inherent in the creative process. Or that risk and fear can be so overwhelming that they end up controlling one’s behavior in such as way as to avoid discomfort. Artists whose work rests at their comfort level—work with which the artist, and/or viewer/consumer can feel comfortable, knowing in advance what they are getting, that presents no challenges to their preconceived notions, and for which they have been assured, their time and/or money is well spent.

Thomas Kincaid, promoted as the “painter of light,” an outlandishly, financially successful artist, would be a good example of this approach, but there are those in all creative fields who fit into this category.

For the remainder of this presentation, I will not be referring to the kind of practice that finds a comfortable resting place and stakes claim to it. Rather I would like to talk about the kind of creative practice that is interested in the moment when one is about to step off their place of comfort venturing into the unknown.

That comfort holds little satisfaction is a critical lesson to those artists interested in personal breakthroughs, innovation, and insight. Otherwise one is working from what one already knows and that knowledge is, by definition, limited.

Like the climber stepping out of their comfort zone and back out into the exposure of the rock face without knowing what is ahead—for those artists who can proceed in the face of not knowing, it becomes possible to explore what they could never have anticipated or pre-visualized, and allows for the possibility that something may be revealed by continuing and pushing on with little, if any, idea where they are going or what the results might be.

Some might refer to this approach as the studio as the site of the unconscious. But it is not only personal, psychological insights that occur from this way of working—material invention and new ways of building form also result from what we all have experienced as “happy accidents”—not quite sure where they came from, but delighted they have appeared. In this context, comfort, and perhaps style, would seem to be in opposition to these possibilities, working at cross-purposes to the potential for real innovation and discovery.

What else can be learned from moving out of one’s comfort zone and proceeding despite one’s fears? This is important to all students and fledgling artists. At some point we all come face to face with the choice: do we seek our potential, or do we seek approval? Though these are not always mutually exclusive, my experience is they are rarely aligned.

Approval … someone left to please, and most likely, over and over again.

We all like confirmation. It is human nature.

In the studio, I often wonder how my work will be received, that is, after wondering if it will ever be received.

What will the viewer think? Or feel?

Perhaps more fearfully, what will the critics think?

If I believe the positive comments, then do I also not have to, at least, entertain, if not believe, the negative ones?

But since any response is out of my control and cannot be managed (after all, that is all I can hope for), then perhaps this is a level of fear I need to toss aside and leave behind.

Though some contemporary artists, and certainly the academy, concern themselves with the “audience,” I know essentially nothing about the audience, and am more likely to guess wrong than right. Who is the audience—educated, middle class, wealthy, white, non-white, older, younger, knows some art history, and on and on … Given all the variables, what does the “audience” have to do with the creative process within the walls of the studio? Can one find their creative and personal voice in the murmurs of the crowd?

Unlike a fear response on the rocks, which is, for the most part, involuntary—the kinds of fears faced in the studio are ones I have some say in—what I have some control over is my own response to pursuing my process.

Can I be myself in the presence of others, real or imagined? Or do I DUCK for COVER?

I can choose who and what I allow into my studio. If fear in this context is just another word for someone left to please, then it is liberating to create a space in which you have no one to please but yourself. Everything else is everything else and outside the studio.

Another important lesson is adaptability; One lower case one can sit on the ground before a climb in front of a rock face and map out move by move the “best” route up the rock to the top, the conclusion of the climb. This is a common activity before climbing. Not only is it prudent and helpful, especially in getting started, it can also lessen the anticipatory anxiety.

However, a few feet off the ground, with cold, hard rock just inches from one’s nose—the view is surprisingly different, and if you are not able to adjust to the situation as it is now presented, your only recourse is to go down and start again, this time, hopefully, with the knowledge that very different solutions may only be apparent when you are confronted by obstacles up close—and that part, maybe even all of the planning and strategizing you have done may have to be scrapped as challenges and opportunities present themselves along the way. At that point, you can choose to remain with the original plan, the one that did not work, but is, after all, the one you know, or you can make adjustments along the way that ensure a better chance at success.

The ability to adjust to circumstances as they present themselves along the way is equally important in the studio. While it is commonly assumed that the best way to solve a difficult problem is to maintain focus, minimize distractions and pay attention to only the relevant details, sticking with the plan as devised—this clenched and rigid state of mind may inhibit just the sort of creative connections that lead to sudden breakthroughs. I want to refer here to an article by Jonathan Lehrer titled, “The Eureka Hunt,” about the biological, neural nature of insight (New Yorker, 07/28/2008).

Focusing on the details while ignoring the bigger picture or, conversely, focusing on the big picture while ignoring the details can disrupt the insight process and preclude an opportunity for something serendipitous to happen. It is important to be able to stay alert to not only recognize, but seize upon the unexpected and remain open to its possibilities in helping you move along in your process, or even point that process, perhaps radically, in another direction. This can be especially helpful when your process appears to have run up against itself or into a wall and is closing down. The experience of fear associated with not knowing what to do at such a time, can prevent you from, to quote Jim Morrison of The Doors, “break on through to the other side.”

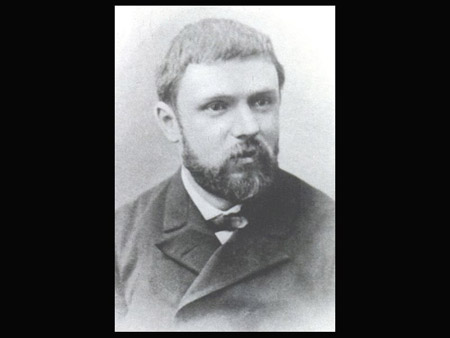

Neurological studies into the nature of insight have shown that coming to an impasse is an important ingredient in the promotion of insight. Rather than reacting in frustration or fear, the place of impasse can be viewed as an exciting opportunity for creation and discovery. In fact, Henri Poincaré insisted that the best way to think about complex problems is to immerse yourself in the problem until you hit an impasse.

When an artist gets to this point in their process, he or she has the choice to relinquish the control they have maintained, or, at least, relax, and though still focused on the task at hand, allow for other options, ones not anticipated that may be better than the original idea(s). It is here adaptability is crucial to success. An impasse can result in a number of thoughts and/or actions—retreat, remorse, regroup … and more. But why not rejoice? Now you are free to do anything you want. You are already at an impasse. It cannot get any worse. The impasse sets you free.

And here is a lovely lesson I learned from the rocks: There are many ways to the top, none of which lands you a millimeter higher than another.

At the same time, as I mentioned earlier, not all lessons are transferable. Very few things, if any, translate 1:1.

For instance, while there is real risk on a rock climb, I maintain there is virtually no risk in the safety of one’s studio. An artist’s life is not in danger if he or she uses the wrong brush, puts the wrong color in the wrong place, or even the right place, over-paints a picture or uses burlap instead of linen. They may project fear and risk onto the canvas and into their process, but nothing they choose to do is as unforgiving as many choices one makes on a climb may be.

When climbing, one always falls twice as far as the climber is from the last anchor of protection. Depending on the length of rope, this can be a small or considerable distance. But no distance is without real danger of bodily harm. And the terrifying moments of a free fall, or the experience of having your skin scraped off while sliding down a rockface, or worse, hitting your head or breaking a bone—are in no way comparable to an emotionally charged decision one makes in the studio. This single bit of knowledge can be completely liberating for one’s studio practice.

So for two weeks we climbed daily, spent afternoons in the studio and discussed those experiences over dinner.

Fear is real, it is a necessary and important part of life, of staying safe, protecting oneself on many levels from many kinds of danger. At the same time, it can be a disintegrating force in living that life to our creative potential if we are unable or unwilling to grant ourselves the permission to exist without fear, or despite it—to simply be, especially in the privacy and safety of where you work.

In light of everything there is to reasonably fear—what are we really afraid of in the studio?

Who is really left to please, but ourselves?

But do not believe me. Ask any first or second grader.

back to top of page

|